Verso (framed)

Verso (framed)

Canaletto - the Piazza from the Piazzetta with the Campanile and the south Side of San Marco RCIN 400516 – Royal Collection Trust

Canaletto - the Piazza from the Piazzetta with the Campanile and the south Side of San Marco RCIN 400516 – Royal Collection Trust

Piazza San Marco, 11 January 2024 at 5 pm...

Piazza San Marco, 11 January 2024 at 5 pm...

Giacomo Guardi Italian School, 1764-1835

10.7 x 17.7 cm

Plus d'images

In this tempera "postcard", Giacomo Guardi, Francesco's son and the last artist of the dynasty, offers us a view of Piazza San Marco inspired by a painting by Canaletto. The artist bathes this urban landscape in the rosy light of late afternoon, as evening begins to fall and the shadows lengthen.

The indication on the verso explains where this panoramic view is supposed to have been taken from : in front of the Doge's Palace, looking towards the campanile. The lack of distance at this point means that the campanile had to be cut off, lending a certain "photographic" modernity to this vedutina, which has probably been executed at the very beginning of the 19th century.

We would like to thank Carolina Trupiano Kowalczyk for her help with the photo of Piazza San Marco.

1. Giacomo Guardi, or the difficulty of being the son of a genius (of painting)

Little is known about the life of Giacomo Guardi, born in Venice in 1764 to relatively elderly parents (his father Francesco was fifty-one and his mother Maria Mathea Pagani thirty-eight). Modestly gifted, he shared his father's studio for some ten years, from the early 1780s until the latter's death on January 1, 1793, first as an apprentice and then as a collaborator.

Unlike his first cousin Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727 - 1804), who helped his father with his large-scale fresco projects, Giacomo Guardi found it difficult to free himself from his father's tutelage. His father did not hesitate to sign his son's paintings with his own name to make them more marketable, and had authorized his son to do the same (only one canvas is known to have been signed with Giacomo Guardi's name[1] ), and Giacomo Guardi did not hesitate to complete drawings left unfinished by his father to make them more attractive, while signing them with his father's name...

It was probably after his father's death that he gave up painting to devote himself entirely to the production of vedutine, these small views of Venice which, together with the sale of the artworks left by his father, would provide him with an income for the rest of his life. He died in 1835, with no heir, and was succeeded by his first cousin Nicolo Guardi (1773 - 1860).

2. The Vedutine

These "small views", executed in black and white or with tempera colors, are the most original aspect of Giacomo Guardi's production. Like his cousin Lorenzo Tiepolo with pastels, Guardi seems to have found in tempera the medium best suited to his abilities. Seeking to render Venetian sites realistically and meticulously, he enlivened them with a host of soberly sketched characters in contemporary dress (some sixty figures and four dogs in the one we are presenting, a detail of which is reproduced below), confering them an undeniable naive charm.

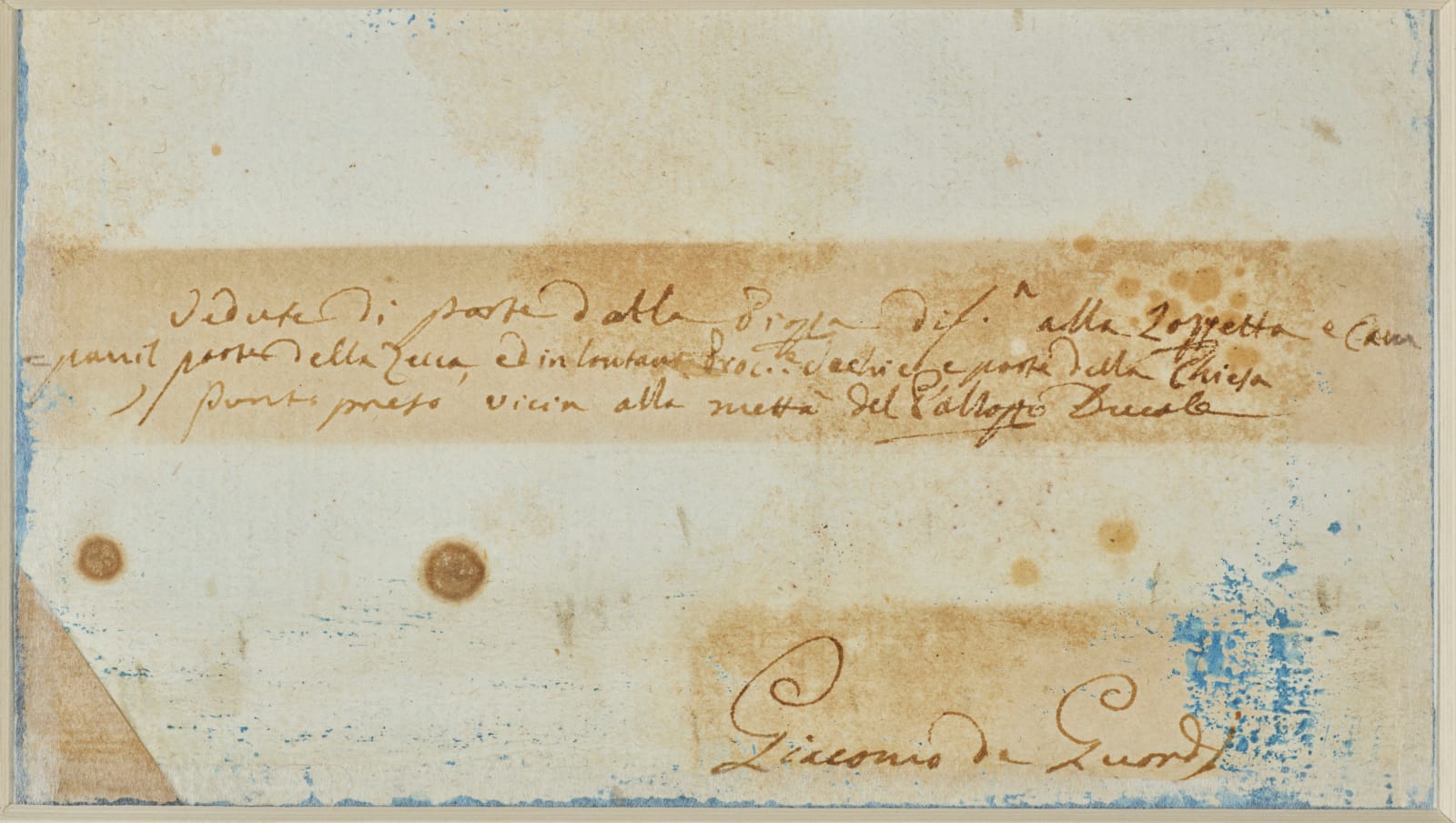

"Postcards" equivalent bought by "foreign" travelers (in Venice, anyone who wasn't Venetian was necessarily a foreigner) from Italy, England, France or Germany, these vedutine were not intended to be sent by mail, but were prized travel souvenirs, to be pasted into albums (most of which have now been dismembered) or framed once back in the mother country. They are usually signed on the back "Giacomo de Guardi", in reference to the noble title granted to the family by the Emperor in 1643. The signature is usually preceded by a few lines explaining the exact location of the view and the monuments depicted, and sometimes even the artist's address!

Most of them have been executed in the same turquoise chromatic range, a very luminous but a little unreal one ("lunar" to use Morassi's expression). The one we present is characterized by a magnificent atmospheric rendering of the dewy light of a fine late afternoon.

3. An unusual view of Piazza San Marco

Giacomo Guardi presents an unusual view of Piazza San Marco, the center of Venetian life past and present. He probably drew his inspiration from a painting by Canaletto dated 1744, engraved by Visentini (whose preparatory drawing is kept in the Correr Museum in Venice).

As in Canaletto's painting, the view is taken from a high vantage point, and several views have been combined to obtain a complete panorama, which would be impossible from a single vantage point. Today, only a panoramic effect allows you to take a similar photo, standing slightly inside the gallery of the Doge's Palace.

On the verso, Giacomo Guardi lists the main surrounding buildings: in the center, the Campanile with the Loggetta at its feet; on the left, the Zecca (mint) building, which is invisible because it stands behind Sansovino's Libreria; in the background, the Ancient Procuraties, which line the north side of Piazza San Marco; and finally, on the right, the southwest corner of the San Marco Basilica.

San Marco was known as the Palatine Church (chiesa palatina) of the Doge's Palace until 1807, when it was elevated to the rank of cathedral basilica. This name ("Chiesa") used by Guardi in the description on the verso suggests that our view was executed at the very beginning of the 19th century, a fact corroborated by the absence of Austrian uniforms, so common in Giacomo Guardi's views dating from after 1815 (the date when Venice became part of the Austrian Empire).

4. Framing

To frame this vedutina, we have chosen a Canaletto-style Venetian frame in carved and gilded wood.

Main bibliographical references :

Antonio Morassi - L'opera completa di Antonio e Francesco Guardi - Alfieri Venezia 1973

Dario Succi - Guardi Itinerario artistico - Editoriale Giorgio Mondatori 2021

[1] Dario Succi - Guardi Itinerario artistico page 436