This section provides access to a detailed description of some of the artworks. Click on the corresponding photo and then on "essay" to have access to this detailed description. This description can be downloaded using "download PDF".

Please note that for some artworks shown on the Artworks page this description is only available on request. To require a description, please click on the photo under "artwork" and then on "enquire".

-

Workshop of Moral and Love Themes (Atelier des thèmes moraux et amoureux)

-

Alessandro Oliverio

-

Biagio Pupini

-

Giuseppe Porta detto Salviati

-

Santi di Tito

-

Tiziano Vecelli, called Titian/ Tiziano Vecelli dit Titien

-

Jan Brueghel the Younger

-

Casper Casteleyn

-

Frans Francken the Younger/ Frans Francken II

-

Claude Lorrain/ Claude Gellée dit Le Lorrain

-

Carlo Francesco Nuvolone

-

David Téniers II

-

Adeodato Zuccati

-

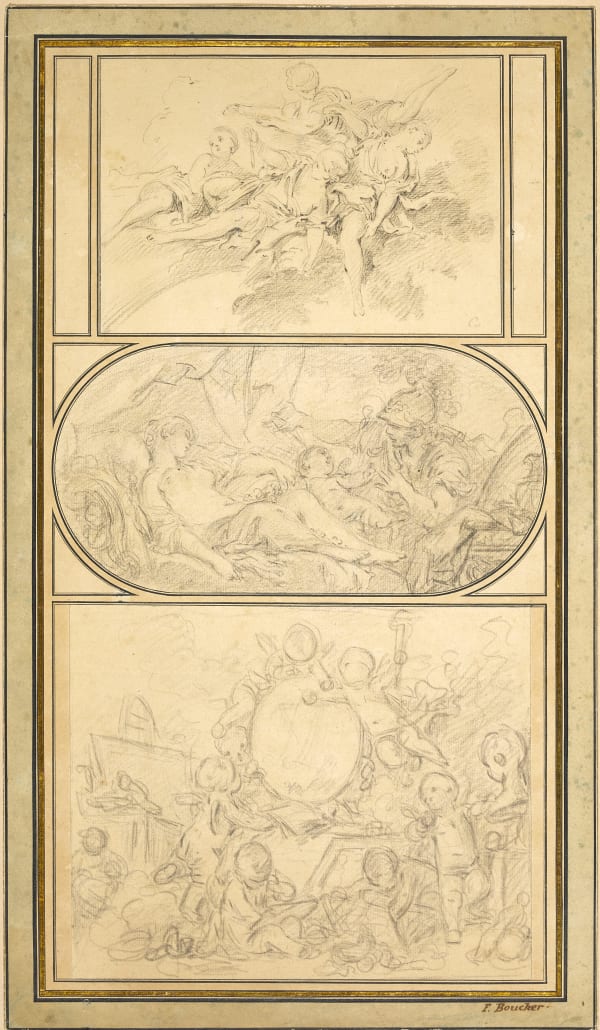

François Boucher

-

Jean-Honoré Fragonard

-

Giacomo Zoffoli

-

Eugène Delacroix

-

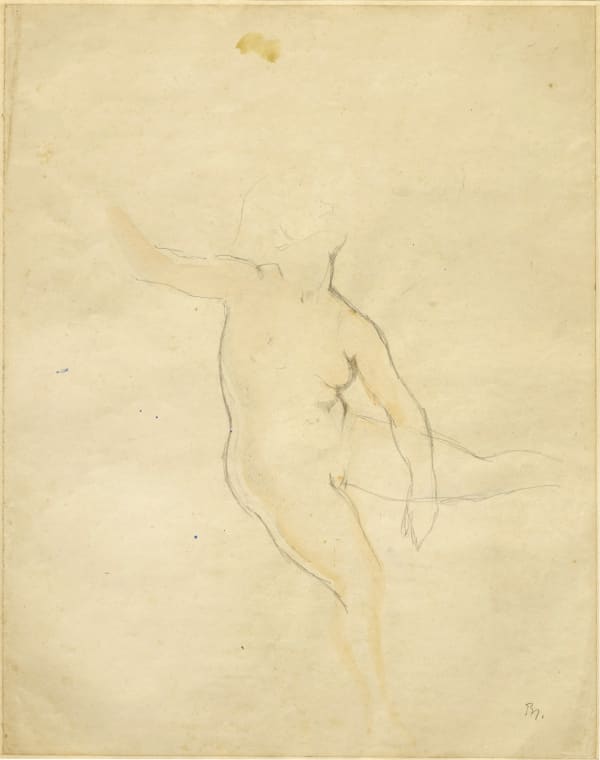

Théodore Géricault

-

Paul Helleu

-

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, dit Balthus